- TypeScript. Мощь never

- Что такое never

- Система типов

- Контроль будущих изменений

- Ограничение контекста: this + never

- Ожидания

- Инварианты

- Гибкая обязательность

- Более строгая проверка

- Заключение

- TypeScript Basics: Understanding The «never» Type

- Characteristics of “never”

- “never” in functions

- Difference between “never” and “void”

- “never” as the variable guard

- Exhaustive Checks

- Conclusion

TypeScript. Мощь never

Когда я впервые увидел слово never, то подумал, насколько бесполезный тип появился в TypeScript. Со временем, все глубже погружаясь в ts, стал понимать, какой мощью обладает это слово. А эта мощь рождается из реальных примеров использования, которыми я намерен поделиться с читателем. Кому интересно, добро пожаловать под кат.

Что такое never

Если окунуться в историю, то мы увидим, что тип never появился на заре TypeScript версии 2.0, с достаточно скромным описанием его предназначения. Если кратко и вольно пересказать версию разработчиков ts, то тип never — это примитивный тип, который олицетворяет собой признак для значений, которых никогда не будет. Или, признак для функций, которые никогда не вернут значения, то ли по причине ее зацикленности, например, бесконечный цикл, то ли по причине ее прерывания. И чтобы наглядно показать суть сказанного, предлагаю посмотреть пример ниже:

/** Пример с прерыванием */ function error(message: string): never < throw new Error(message); >/** Бесконечный цикл */ function infiniteLoop(): never < while (true) < >> /** Божественная рекурсия */ function infiniteRec(): never

Возможно из-за таких примеров, у меня и сложилось первое впечатление, что тип нужен для наглядности.

Система типов

Сейчас я могу утверждать, что богатая фауна системы типов в TypeScript в том числе — это заслуга never. И в подтверждение своих слов приведу несколько библиотечных типов из lib.es5.d.ts

/** Exclude from T those types that are assignable to U */ type Exclude = T extends U ? never : T; /** Extract from T those types that are assignable to U */ type Extract = T extends U ? T : never; /** Construct a type with the properties of T except for those in type K. */ type Omit = Pick>; /** Exclude null and undefined from T */ type NonNullable = T extends null | undefined ? never : T; /** Obtain the parameters of a function type in a tuple */ type Parameters any> = T extends (. args: infer P) => any ? P : never; Из своих типов с never приведу любимый — GetNames, усовершенствованный аналог keyof:

/** * GetNames тип для извлечения набора ключей * @template FromType тип - источник ключей * @template KeepType критерий фильтрации * @template Include признак для указания как интерпретировать критерий фильтрации. В случае false - инвертировать результат для KeepType */ type GetNames = < [K in keyof FromType]: FromType[K] extends KeepType ? Include extends true ? K : never : Include extends true ? never : K >What is never in typescript; // Пример использования class SomeClass < firstName: string; lastName: string; age: number; count: number; getData(): string < return "dummy"; >> // be: "firstName" | "lastName" type StringKeys = GetNames; // be: "age" | "count" type NumberKeys = GetNames; // be: "getData" type FunctionKeys = GetNames; // be: "firstName" | "lastName" | "age" | "count" type NonFunctionKeys = GetNames; Контроль будущих изменений

Когда жизнь проекта не скоротечна, разработка приобретает особый характер. Хочется иметь контроль над ключевыми моментами в коде, иметь гарантии того, что Вы или члены Вашей команды не забудут поправить жизненно важный участок кода, когда этого потребует время. Такие участки кода особенно проявляют себя, когда есть состояние или перечисление чего-либо. Например, перечисление набора действий над некой сущностью. Предлагаю взглянуть на пример, для понимания контекста происходящего.

// Некий набор действий - может жить далеко, даже не в том проекте, что и ActionEngine type AdminAction = "CREATE" | "ACTIVATE"; // Место, где этот набор действий обрабатывается, хотя тип AdminAction определен неизвестно где. class ActionEngine < doAction(action: AdminAction) < switch (action) < case "CREATE": // логика здесь return "CREATED"; case "ACTIVATE": // логика здесь return "ACTIVATED"; default: throw new Error("Этого не должно случиться"); >> > Код выше упрощен настолько, насколько это возможно только для того, чтобы акцентировать внимание на важном моменте — тип AdminAction определен в другом проекте и даже возможно, что сопровождается не Вашей командой. Так как проект будет жить долгое время, необходимо уберечь свой ActionEngine от изменений в типе AdminAction без Вашего ведома. TypeScript для решения такой задачи предлагает несколько рецептов, один из которых — использовать тип never. Для этого нам потребуется определить NeverError и использовать его в методе doAction.

class NeverError extends Error < // если дело дойдет до вызова конструктора с параметром - ts выдаст ошибку constructor(value: never) < super(`Unreachable statement: $`); > > class ActionEngine < doAction(action: AdminAction) < switch (action) < case "CREATE": // логика здесь return "CREATED"; case "ACTIVATE": // логика здесь return "ACTIVATED"; default: throw new NeverError(action); // ^ контролирует здесь что все варианты в switch блоке определены. >> > Теперь добавьте в AdminAction новое значение «BLOCK» и получите ошибку на этапе компиляции: Argument of type ‘«BLOCK»’ is not assignable to parameter of type ‘never’.ts(2345).

В принципе мы этого и добивались. Стоит упомянуть интересный момент, что от изменения элементов AdminAction или удаления из набора нас защищает конструкция switch. Из практики использования могу сказать, что это действительно работает так как ожидается.

Если нет желания вводить класс NeverError, то можно контролировать код через объявление переменной с типом never. Вот так:

type AdminAction = "CREATE" | "ACTIVATE" | "BLOCK"; class ActionEngine < doAction(action: AdminAction) < switch (action) < case "CREATE": // логика здесь return "CREATED"; case "ACTIVATE": // логика здесь return "ACTIVATED"; default: const unknownAction: never = action; // Type '"BLOCK"' is not assignable to type 'never'.ts(2322) throw new Error(`Неизвестный тип действия $`); > > > Ограничение контекста: this + never

Следующий прием часто спасает меня от нелепых ошибок на фоне усталости или невнимательности. В примере ниже, я не буду давать оценку качества выбранного подхода. У нас де-факто, такое встречается. Предположим, Вы используете метод в классе, который не имеет доступа к полям класса. Да, звучит страшно — все это гов… код.

@SomeDecorator() class SomeUiPanel < @Inject private someService: SomeService; public beforeAccessHook() < // Не смотря на то, что метод не статический, ему недоступны поля класса SomeUiPanel this.someService.doInit("Bla bla"); // ^ приведет к ошибки на этапе выполнения кода: метод beforeAccessHook вызывается в контексте, делающий доступ к сервису невозможным >> В более широком кейсе это могут быть callback или стрелочные функции, имеющие свои контексты выполнения. И задача звучит так: Как защитить себя от ошибки времени выполнения? Для этого в TypeScript есть возможность указать контекст this

@SomeDecorator() class SomeUiPanel < @Inject private someService: SomeService; public beforeAccessHook(this: never) < // Не смотря на то, что метод не статический, ему недоступны поля класса SomeUiPanel this.someService.doInit("Bla bla"); // ^ Property 'someService' does not exist on type 'never' >> Справедливости ради, скажу, что это не заслуга never. Вместо него можно использовать и void и <>. Но внимание привлекает именно тип never, когда читаешь код.

Ожидания

Инварианты

Имея определенное представление о never, я думал, что следующий код должен заработать:

type Maybe = T | void; function invariant(condition: Cond, message: string): Cond extends true ? void : never < if (condition) < return; >throw new Error(message); > function f(x: Maybe, c: number) < if (c >0) < invariant(typeof x === "number", "When c is positive, x should be number"); (x + 1); // works because x has been refined to "number" >> Но увы. Выражение (x + 1) выдает ошибку: Operator ‘+’ cannot be applied to types ‘Maybe’ and ‘1’. Сам пример я подсмотрел в статье Переносим 30 000 строк кода с Flow на TypeScript.

Гибкая обязательность

Я думал, что с помощью never могу управлять обязательностью параметров функций и при определенных условий отключать ненужные. Но нет, так не сработает:

function variants(x: Type, c: Type extends number ? number : never): number < if (typeof x === "number") < return x + c; >return +x; > const three = variants(1, 2); // ok // 2 аргумент - never, если первый с типом string. Увы, обязательность сохраняется const one = variants("1"); // expected 2 arguments, but got 1.ts(2554) Выше указанная задача решается другим способом.

Более строгая проверка

Хотелось, чтобы компилятор ts не пропускал такого, как нечто, противоречащее здравому смыслу.

Заключение

В конце, хочу предложить маленькую задачу, из серии странные странности. В какой строке ошибка?

class never < never: never; >const whats = new never(); whats.never = ""; TypeScript Basics: Understanding The «never» Type

The TypeScript never keyword is a bit of a mystery to many developers. What does it do, and when should you use it? Today we will discuss the never keyword in-depth, and cover the situations where you could encounter it.

Characteristics of “never”

TypeScript uses the never keyword to represent situations and control flows that should not logically happen.

In reality, you won’t come across the need to use never in your work very often, but it’s still good to learn how it contributes to type safety in TypeScript.

Let’s see how the documentation describes it: «The never type is a subtype of, and assignable to, every type; however, no type is a subtype of, or assignable to, never (except never itself).»

TLDR; of the above is that you can assign a variable of the type never to any other variable, but you cannot assign other variables to never . Let’s take a look at a code sample:

const throwErrorFunc = () => throw new Error("LOL") >; let neverVar: never = throwErrorFunc() const myString = "" const myInt:number = neverVar; neverVar = myString // Type 'string' is not assignable to type 'never' You can ignore throwErrorFunc for now. Just know that’s a workaround for initializing a variable with type never.

As you can see from the above code, we can assign our variable neverVar of type never to a variable myInt which is of type number . However, we cannot assign the myString variable of type string to neverVar . That will result in a TypeScript error.

You can’t assign variables of any other type to never , even variables of type any .

“never” in functions

TypeScript uses never as a return type for functions that will not reach their return endpoint.

This could mainly happen for two reasons:

const throwErrorFunc = () => throw new Error("LOL") >; // typescript infers the return type of this function to be 'never' Another case is if you have an infinite loop with a truthy expression that doesn’t have any breaks or return statements:

const output = () => while (true) console.log("This will get annoying quickly"); > > // typescript infers the return type of this function to be 'never' In both cases, TypeScript will infer that the return type of these functions is never .

Difference between “never” and “void”

So what about the void type? Why do we even need never if we have void ?

The main difference between never and void is that the void type can have undefined or null as a value.

TypeScript uses void for functions that do not return anything. When you don’t specify a return type for your function, and it doesn’t return anything in any of the code paths, TypeScript will infer that its return type is void .

In TypeScript, void functions that don’t return anything are actually returning undefined .

const functionWithVoidReturnType = () => <>; // typescript infers the return type of this function to be 'void' console.log(functionWithVoidReturnType()); // undefined However, we usually ignore the return values of the void functions.

Another thing to note here: as per the characteristics of the never type we covered earlier, you cannot assign void to never:

const myVoidFunction = () => <> neverVar = myVoidFunction() // ERROR: Type 'never' is not assignable to type 'void' “never” as the variable guard

Variables can become of the type never if they are narrowed by a type guard that can never be true. Usually, this indicates a flaw in your conditional logic.

Let’s take a look at an example:

const unExpectedResult = (myParam: "this" | "that") => if (myParam === "this") > else if (myParam === "that") > else console.log( myParam >) > > In the above example, when the function execution reaches the line console.log(< myParam >) , the type of myParam will be never .

This happens because we’re setting the type of myParam to be either “this” or “that”. Since TypeScript assumes that those two are the only possible choices in this situation, logically, the third else statement should never occur. So TypeScript sets the parameter type to never .

Exhaustive Checks

One of the places you might see never in practice is in exhaustive checks. Exhaustive checks are useful for ensuring that you’ve handled every edge case in your code.

Let’s take a look at how we can add a better type safety to a switch statement using an exhaustive check:

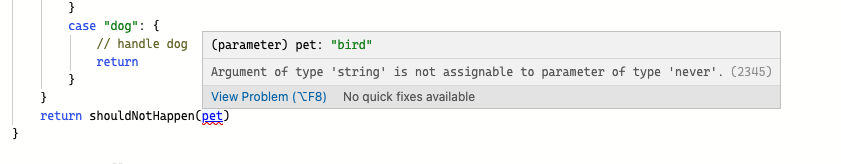

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 type Animal = "cat" | "dog" | "bird" const shouldNotHappen = (animal: never) => throw new Error("Didn't expect to get here") > const myPicker = (pet: Animal) => switch(pet) case "cat": // handle cat return > case "dog": // handle dog return > > return shouldNotHappen(pet) > When you add return shouldNotHappen(pet) , you should immediately see an error:

The error message informs you of the case you forgot to include in your switch statement. It’s a clever pattern for getting compile-time safety and ensuring you handled all the cases in your switch statement.

Conclusion

As you can see, the never type is useful for specific things. Most of the time, it’s an indication that there are flaws in your code.

But in some situations, such as exhaustive checks, it can be a great tool to help you write safer TypeScript code.

If you’d like to get more web development, React and TypeScript tips consider following me on Twitter, where I share things as I learn them.

Happy coding!