Rich text editor

An interface for editing “rich text” content (i.e. with formatting), usually through a WYSIWYG interface.

Table of contents

3 examples

Atlassian Design System

- React

- Code examples

- Usage guidelines

- Tone of voice

- Accessibility

Lightning Design System

- React

- Code examples

- Usage guidelines

- Tone of voice

- Open source

Quasar Framework

The rich text editor is one of the most complex interface components, both visually and technically. Borrowing heavily from desktop word processing software, it has gradually become the primary means of writing blog posts, editing CMS-based websites and even composing emails. Fundamentally, a rich text editor is an interface for editing ‘rich text’. This is text that is richer than ‘plain text’ by virtue of containing formatting information: bold, italic, strikethrough , different fonts, headings, ordered lists, unordered lists, etc.

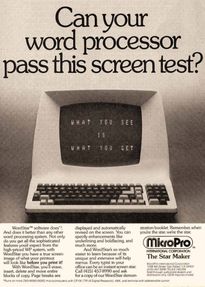

Before the invention of word processing software, adding formatting to text documents meant using a markup language such as TeX. In TeX, you format using commands: e.g. \textit would output «this text is in italics» — what you see while editing is different from what you get as the output. WYSIWYG (pronounced wiz-ee-wig) or «what you see is what you get» editors aim to make the appearance of the content inside the editor resemble the final product as accurately as possible, hiding the formatting code from the user and showing its actual effect instead.

One of the first word processors to label itself as WYSIWYG was WordStar: priced at $495 + $50 for the manual 1 , version 1.0 was released in 1978. In WordStar, the user would apply formatting using ‘Control codes’. For example, pressing Ctrl + P then B (or just F4 if you were lucky enough to own a computer with function keys) would make the text bold. To move through the document, instead of using a mouse, you would use the diamond shaped formation of keys: Ctrl + E , Ctrl + X , Ctrl + S , and Ctrl + D to move the cursor up, down, left or right respectively 2 . Calling WordStar a WYSIWYG editor is a stretch — the formatting visible on screen while editing is limited to line and page breaks. Bold and underline was still represented by inline commands like ^B or ^Y . Later versions added preview functionality so you could get a better idea of the layout of the printed page, but this would take you out of the editing mode.

Arriving soon after WordStar, WordPerfect introduced some improvements to differentiate formatting on screen: displaying bold text brighter than regular text and rendering a line below underlined text.

3

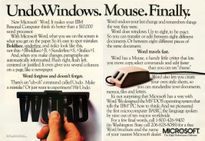

The next major step in the world of WYSIWYG editing was enabled by the humble mouse; although first devised in the 1960s, it wasn’t until the 1980s that mice started to gain popularity. In 1983 Microsoft announced both the The Microsoft mouse ($195) and Multi-Tool Word ($395), a word processor designed to take advantage of the new peripheral (Microsoft would quickly simplify the name to just ‘Word’) 4 . The user no longer needed to type text commands to apply formatting but could instead use their mouse to navigate the Graphical User Interface (GUI), clicking on buttons and menus to apply specific formatting rules.

The year after the release of Microsoft Word, the Apple Macintosh was launched, which came bundled with Apple’s new word processor, MacWrite. Although the feature set was rudimentary by today’s standards, MacWrite had an intuitive mouse-based graphical user interface and boasted the ability to display different fonts and formatting during editing. MacWrite is often called the world’s first WYSIWYG editor, although — as with many of Apple’s greatest successes — it was based on someone else’s idea; in this case a prototype piece of software developed at Xerox PARC (A research centre in Palo Alto, California). Bravo, developed in 1974, 10 whole years before the release of MacWrite, was probably the world’s first WYSIWYG editor. You can hear Steve Jobs speak about his first encounter with a GUI at Xerox PARC in the film, Triumph of the Nerds 5 .

When the web began to be seen as a publishing platform, content writers, designers, and other non-programmers needed a tool to create web content without needing to learn HTML, the markup language of the web. The first WYSIWYG tool for building web pages, WebMagic, arrived in 1995 and was quickly followed by FrontPage (purchased by Microsoft in 1996 for \$133million). These original tools were desktop applications you needed to purchase and install on your computer.

The rise of blogging services around the turn of the millennium meant that a way of editing HTML content in the browser was needed. Some of the earliest browser-based rich text editors include: Mozile (the Mozilla Inline Editor); Bitflux editor; FCKeditor, later renamed to CKEditor (because «the FCK letters combined together are a shortcut for a bad word») and TinyMCE. Web-based rich-text editors have now become the tool of choice (or necessity) for many content writers. Word Processing for print has also moved into the browser with software like Google Docs.

So how do rich text editors actually work? Most modern WYSIWYG editors now make use of the contenteditable html attribute introduced in Internet Explorer 5.5, that when set to true , allows the user to directly edit the content of an HTML element.

Mainly due to the complexity of the task they’re trying to achieve, rich text editors tend to have issues, and over the years they have had their fair share of detractors 6 7 .

As is the case any time that a website accepts user input, you’ve got to assume some of your users have malicious intent; if not you’re opening yourself up to all sorts of exploits including, but not limited to: Cross-site request forgery, SQL injection, and Local/Remote File inclusion.

If you’re showing user input to other users (e.g. displaying the output of a WYSIWYG as comments under an article), there’s a whole new category of threat: Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) attacks. An XSS attack is where JavaScript gets injected into a webpage on an otherwise trusted website, unknown to the end user or owner of the website. This risk of XSS attacks can be minimised my filtering (or sanitizing) the user input before it’s stored or shown to anyone else — this is a process that involves stripping out everything but an explicitly allowed set of characters, HTML tags and attributes — Here’s a handy list of rules for preventing XSS. If you’re not sanitizing user input, you’re gonna have a bad time.

Loss of control over design

WYSIWYG editors take decisions usually made by designers and hands them to the content editor. Although it is possible to lock down users’ options to limit what they can do, rich text editors often ship with a very generous default configuration. It is also uncommon for a rich text editor to reliably enforce semantic best practices such as always including relevant alt attributes on images and using correctly ordered levels for headings.

As with all forms of WYSIWYG, the appearance of content in a rich text editor is usually just an approximation of the final output. Unless you’re applying the exact same CSS (and JS) to the editable content as the output, there are going to be visual discrepancies. Some implementations attempt to get around this issue with a ‘live preview’, showing a rendered version of the output alongside the editor which updates as you type.

Copying and pasting from Word

When a user copies formatted text from one program to another, they generally expect formatting to be retained; but pasting text from one rich text format to another entirely different rich text format is not a simple task. It often results in bloated markup filled with characters and unnecessary HTML elements.

Making JavaScript-driven applications accessible requires work, especially when accessibility is not seen as a key requirement from the beginning of development. The new editor in WordPress 5.0, Gutenberg, has been plagued by accessibility problems.

Due to the complex logic required to build a rich text editor, I’d highly recommend not attempting to build one from scratch. It’s usually best to find an existing example and adapt it to your needs. Here are some of the most popular libraries available today:

- CKEditor: First released in 2003, CKEditor was one of the earliest web-based WYSIWYG editors. It has constantly improved over the proceeding years adding features such as a special ‘paste from Word’ plugin and comprehensive support for keyboard access and assistive technology. It also has a number of integrations with front-end frameworks such as React and Vue.

- Quill is a modern editor which uses its own document model, parchment, an abstraction layer that sits parallel to the DOM (Document Object Model).

- ProseMirror brands itself as «A toolkit for building rich-text editors on the web»; not really WYSIWYG editor as such, it is more a collection of modules for building your own. Similar to Quill, the document itself is abstracted into a custom data structure. Immensely powerful but definitely not a simple drop-in solution.

You can view a pretty comprehensive list of WYSIWYG editors at the Awesome WYSIWYG repo.

HTML is the markup language of the world wide web. If you want precise control over what ends up in the browser, there are some things that you can only achieve through hand-coded HTML. If you find the syntax too verbose or slow to write, there are plenty of tools that can speed up the process:

- Emmet lets you type short CSS-selector-like expressions which, when expanded, output HTML syntax. It is commonly installed as a text-editor extension.

- Haml and Pug are templating languages which use indentation to represent element nesting instead of opening and closing tag pairs. They are designed to be cleaner and easier to read than the equivalent HTML.

Markdown is another markup language, but what sets it apart is the readability of its syntax. The goal behind markdown is that the formatting can be interpreted even in the original markup. It borrows heavily from existing conventions for marking up plain text in emails and online forums. e.g. _italics_ , **bold** , # Headings , and starting lines with > to indicate a blockquote 8 . Its simple design allows it to be converted to many output formats, not just HTML. See also: Textile, a precursor to Markdown with some syntax in common.

Unfortunately, while much of the Markdown syntax is intuitive, there are certain patterns that are definitely not: the syntax for adding a link feels slightly arbitrary and is hard to remember; and adding markup that is not covered by Markdown’s syntax requires the use of HTML.

In some cases it’s inevitable that a rich text editor is the best, or only, tool for the job. There are also other times where an alternative, such as Markdown or even plain text is a better (and simpler to implement) solution. My advice is to try a few libraries and choose the one that works best for your application and your users; lock down the formatting options to only the bare minimum of what is necessary; and always filter the output.

- Word-Star BYTE (advertisement). January 1980. p. 49.↩

- WordStar: A writer’s word processorRobert J. Sawyer↩

- Micosoft Word BYTE (advertisement). December 1983. p. 88-9.↩

- Mouse and new WP program join Microsoft product lineup. 1983↩

- Steve Jobs talks about his 1979 visit to Xerox PARC↩

- Your WYSIWYG Editor sucksRachel Andrew↩

- What’s wrong with WYSIWYGAdam Hyde↩

- Markdown: Syntax↩