Namespaces

A note about terminology: It’s important to note that in TypeScript 1.5, the nomenclature has changed. “Internal modules” are now “namespaces”. “External modules” are now simply “modules”, as to align with ECMAScript 2015’s terminology, (namely that module X < is equivalent to the now-preferred namespace X < ).

This post outlines the various ways to organize your code using namespaces (previously “internal modules”) in TypeScript. As we alluded in our note about terminology, “internal modules” are now referred to as “namespaces”. Additionally, anywhere the module keyword was used when declaring an internal module, the namespace keyword can and should be used instead. This avoids confusing new users by overloading them with similarly named terms.

Let’s start with the program we’ll be using as our example throughout this page. We’ve written a small set of simplistic string validators, as you might write to check a user’s input on a form in a webpage or check the format of an externally-provided data file.

Validators in a single file

ts

As we add more validators, we’re going to want to have some kind of organization scheme so that we can keep track of our types and not worry about name collisions with other objects. Instead of putting lots of different names into the global namespace, let’s wrap up our objects into a namespace.

In this example, we’ll move all validator-related entities into a namespace called Validation . Because we want the interfaces and classes here to be visible outside the namespace, we preface them with export . Conversely, the variables lettersRegexp and numberRegexp are implementation details, so they are left unexported and will not be visible to code outside the namespace. In the test code at the bottom of the file, we now need to qualify the names of the types when used outside the namespace, e.g. Validation.LettersOnlyValidator .

ts

As our application grows, we’ll want to split the code across multiple files to make it easier to maintain.

Here, we’ll split our Validation namespace across many files. Even though the files are separate, they can each contribute to the same namespace and can be consumed as if they were all defined in one place. Because there are dependencies between files, we’ll add reference tags to tell the compiler about the relationships between the files. Our test code is otherwise unchanged.

ts

ts

ts

ts

Once there are multiple files involved, we’ll need to make sure all of the compiled code gets loaded. There are two ways of doing this.

First, we can use concatenated output using the outFile option to compile all of the input files into a single JavaScript output file:

tsc --outFile sample.js Test.ts

The compiler will automatically order the output file based on the reference tags present in the files. You can also specify each file individually:

tsc --outFile sample.js Validation.ts LettersOnlyValidator.ts ZipCodeValidator.ts Test.ts

Alternatively, we can use per-file compilation (the default) to emit one JavaScript file for each input file. If multiple JS files get produced, we’ll need to use tags on our webpage to load each emitted file in the appropriate order, for example:

html

Another way that you can simplify working with namespaces is to use import q = x.y.z to create shorter names for commonly-used objects. Not to be confused with the import x = require(«name») syntax used to load modules, this syntax simply creates an alias for the specified symbol. You can use these sorts of imports (commonly referred to as aliases) for any kind of identifier, including objects created from module imports.

ts

Notice that we don’t use the require keyword; instead we assign directly from the qualified name of the symbol we’re importing. This is similar to using var , but also works on the type and namespace meanings of the imported symbol. Importantly, for values, import is a distinct reference from the original symbol, so changes to an aliased var will not be reflected in the original variable.

Working with Other JavaScript Libraries

To describe the shape of libraries not written in TypeScript, we need to declare the API that the library exposes. Because most JavaScript libraries expose only a few top-level objects, namespaces are a good way to represent them.

We call declarations that don’t define an implementation “ambient”. Typically these are defined in .d.ts files. If you’re familiar with C/C++, you can think of these as .h files. Let’s look at a few examples.

The popular library D3 defines its functionality in a global object called d3 . Because this library is loaded through a tag (instead of a module loader), its declaration uses namespaces to define its shape. For the TypeScript compiler to see this shape, we use an ambient namespace declaration. For example, we could begin writing it as follows:

ts

The TypeScript docs are an open source project. Help us improve these pages by sending a Pull Request ❤

Модули и пространства имен

Для организации больших программ предназначены пространства имен. Пространства имен содержат группу классов, интерфейсов, функций, других пространств имен, которые могут использоваться в некотором общем контексте.

Для определения пространств имен используется ключевое слово namespace :

В данном случае пространство имен называется Personnel , и оно содержит класс Employee. Чтобы типы и объекты, определенные в пространстве имен, были видны извне, они определяются с ключевым словом export . В этом случае во вне мы сможем использовать класс Employee:

namespace Personnel < export class Employee < constructor(public name: string)< >> > let alice = new Personnel.Employee("Alice"); console.log(alice.name); // Alice При этом пространства имен могут содержать и интерфейсы, и объекты, и функции, и даже обычные переменные и константы:

namespace Personnel < export interface IUser< displayInfo(): void; >export class Employee < constructor(public name: string)< >> export function work(emp: Employee) : void < console.log(emp.name, "is working"); >export let defaultUser= < name: "Kate" >export let value = "Hello"; > let tom = new Personnel.Employee("Tom") Personnel.work(tom); // Tom is working console.log(Personnel.defaultUser.name); // Kate console.log(Personnel.value); // Hello Пространство имен в отдельном файле

Нередко пространства имен определяются в отдельных файлах. Например, определим файл personnel.ts со следующим кодом:

namespace Personnel < export class Employee < constructor(public name: string)< >> export class Manager < constructor(public name: string)< >> >

И в той же папке определим главный файл приложения app.ts :

/// let tom = new Personnel.Employee("Tom") console.log(tom.name); let sam = new Personnel.Manager("Sam"); console.log(sam.name); С помощью директивы /// подключается файл personnel.ts.

Далее нам надо объединить оба файла в один файл, который затем можно подключать на веб-страницу. Для этого при компиляции указывается опция:

--outFile target.js sourse1.ts source2.ts source3.ts .

Опции outFile в качестве первого параметра передается название файла, который будет генерироваться. А последующие параметры — файлы с кодом TypeScript, которые будут компилироваться.

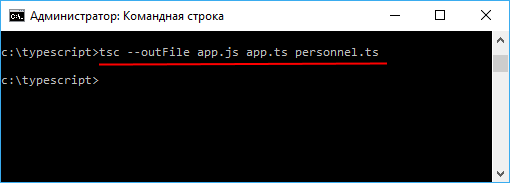

То есть в данном случае нам надо выполнить в консоли команду

tsc --outFile app.js app.ts personnel.ts

В итоге будет создан один файл app.js.

Вложенные пространства имен

Пространства имен могут быть вложенными:

namespace Data < export namespace Personnel < export class Employee < constructor(public name: string)< >> > export namespace Clients < export class VipClient < constructor(public name: string)< >> > > let tom = new Data.Personnel.Employee("Tom") console.log(tom.name); let sam = new Data.Clients.VipClient("Sam"); console.log(sam.name); Причем вложенные пространства имен определяются со словом export . Соответственно при обращении к типам надо использовать все пространства имен.

Псевдонимы

Возможно, нам приходится создавать множество объектов Data.Personnel.Employee , но каждый раз набирать полное имя класса с учетом пространств имен, вероятно, не всем понравиться, особенно когда модули имеют глубокую вложенность по принципу матрешки. Чтобы сократить объем кода, мы можем использовать псевдонимы, задаваемые с помощью ключевого слова import . Например:

namespace Data < export namespace Personnel < export class Employee < constructor(public name: string)< >> > > import employee = Data.Personnel.Employee; let tom = new employee("Tom") console.log(tom.name); После объявления псевдонима employee будет рассматриваться как краткое имя для Data.Personnel.Employee .