- constructor

- Try it

- Syntax

- Description

- Examples

- Using the constructor

- Calling super in a constructor bound to a different prototype

- Specifications

- Browser compatibility

- See also

- JavaScript Constructors: What You Need to Know

- What Happens When A Constructor Gets Called?

- JavaScript Constructor Examples

- Using the «this» Keyword

- Create Multiple Objects

- Constructor with Parameters

- Constructor vs Object Literal

- Object Prototype

- Built-in Constructors

- Track, Analyze and Manage Errors With Rollbar

constructor

The constructor method is a special method of a class for creating and initializing an object instance of that class.

Note: This page introduces the constructor syntax. For the constructor property present on all objects, see Object.prototype.constructor .

Try it

Syntax

constructor() /* … */ > constructor(argument0) /* … */ > constructor(argument0, argument1) /* … */ > constructor(argument0, argument1, /* … ,*/ argumentN) /* … */ >

There are some additional syntax restrictions:

- A class method called constructor cannot be a getter, setter, async, or generator.

- A class cannot have more than one constructor method.

Description

A constructor enables you to provide any custom initialization that must be done before any other methods can be called on an instantiated object.

class Person constructor(name) this.name = name; > introduce() console.log(`Hello, my name is $this.name>`); > > const otto = new Person("Otto"); otto.introduce(); // Hello, my name is Otto

If you don’t provide your own constructor, then a default constructor will be supplied for you. If your class is a base class, the default constructor is empty:

If your class is a derived class, the default constructor calls the parent constructor, passing along any arguments that were provided:

constructor(. args) super(. args); >

Note: The difference between an explicit constructor like the one above and the default constructor is that the latter doesn’t actually invoke the array iterator through argument spreading.

That enables code like this to work:

class ValidationError extends Error printCustomerMessage() return `Validation failed :-( (details: $this.message>)`; > > try throw new ValidationError("Not a valid phone number"); > catch (error) if (error instanceof ValidationError) console.log(error.name); // This is Error instead of ValidationError! console.log(error.printCustomerMessage()); > else console.log("Unknown error", error); throw error; > >

The ValidationError class doesn’t need an explicit constructor, because it doesn’t need to do any custom initialization. The default constructor then takes care of initializing the parent Error from the argument it is given.

However, if you provide your own constructor, and your class derives from some parent class, then you must explicitly call the parent class constructor using super() . For example:

class ValidationError extends Error constructor(message) super(message); // call parent class constructor this.name = "ValidationError"; this.code = "42"; > printCustomerMessage() return `Validation failed :-( (details: $this.message>, code: $this.code>)`; > > try throw new ValidationError("Not a valid phone number"); > catch (error) if (error instanceof ValidationError) console.log(error.name); // Now this is ValidationError! console.log(error.printCustomerMessage()); > else console.log("Unknown error", error); throw error; > >

Using new on a class goes through the following steps:

- (If it’s a derived class) The constructor body before the super() call is evaluated. This part should not access this because it’s not yet initialized.

- (If it’s a derived class) The super() call is evaluated, which initializes the parent class through the same process.

- The current class’s fields are initialized.

- The constructor body after the super() call (or the entire body, if it’s a base class) is evaluated.

Within the constructor body, you can access the object being created through this and access the class that is called with new through new.target . Note that methods (including getters and setters) and the prototype chain are already initialized on this before the constructor is executed, so you can even access methods of the subclass from the constructor of the superclass. However, if those methods use this , the this will not have been fully initialized yet. This means reading public fields of the derived class will result in undefined , while reading private fields will result in a TypeError .

new (class C extends class B constructor() console.log(this.foo()); > > #a = 1; foo() return this.#a; // TypeError: Cannot read private member #a from an object whose class did not declare it // It's not really because the class didn't declare it, // but because the private field isn't initialized yet // when the superclass constructor is running > >)();

The constructor method may have a return value. While the base class may return anything from its constructor, the derived class must return an object or undefined , or a TypeError will be thrown.

class ParentClass constructor() return 1; > > console.log(new ParentClass()); // ParentClass <> // The return value is ignored because it's not an object // This is consistent with function constructors class ChildClass extends ParentClass constructor() return 1; > > console.log(new ChildClass()); // TypeError: Derived constructors may only return object or undefined

If the parent class constructor returns an object, that object will be used as the this value on which class fields of the derived class will be defined. This trick is called «return overriding», which allows a derived class’s fields (including private ones) to be defined on unrelated objects.

The constructor follows normal method syntax, so parameter default values, rest parameters, etc. can all be used.

class Person constructor(name = "Anonymous") this.name = name; > introduce() console.log(`Hello, my name is $this.name>`); > > const person = new Person(); person.introduce(); // Hello, my name is Anonymous

The constructor must be a literal name. Computed properties cannot become constructors.

class Foo // This is a computed property. It will not be picked up as a constructor. ["constructor"]() console.log("called"); this.a = 1; > > const foo = new Foo(); // No log console.log(foo); // Foo <> foo.constructor(); // Logs "called" console.log(foo); // Foo

Async methods, generator methods, accessors, and class fields are forbidden from being called constructor . Private names cannot be called #constructor . Any member named constructor must be a plain method.

Examples

Using the constructor

This code snippet is taken from the classes sample (live demo).

class Square extends Polygon constructor(length) // Here, it calls the parent class' constructor with lengths // provided for the Polygon's width and height super(length, length); // NOTE: In derived classes, `super()` must be called before you // can use `this`. Leaving this out will cause a ReferenceError. this.name = "Square"; > get area() return this.height * this.width; > set area(value) this.height = value ** 0.5; this.width = value ** 0.5; > >

Calling super in a constructor bound to a different prototype

super() calls the constructor that’s the prototype of the current class. If you change the prototype of the current class itself, super() will call the constructor that’s the new prototype. Changing the prototype of the current class’s prototype property doesn’t affect which constructor super() calls.

class Polygon constructor() this.name = "Polygon"; > > class Rectangle constructor() this.name = "Rectangle"; > > class Square extends Polygon constructor() super(); > > // Make Square extend Rectangle (which is a base class) instead of Polygon Object.setPrototypeOf(Square, Rectangle); const newInstance = new Square(); // newInstance is still an instance of Polygon, because we didn't // change the prototype of Square.prototype, so the prototype chain // of newInstance is still // newInstance --> Square.prototype --> Polygon.prototype console.log(newInstance instanceof Polygon); // true console.log(newInstance instanceof Rectangle); // false // However, because super() calls Rectangle as constructor, the name property // of newInstance is initialized with the logic in Rectangle console.log(newInstance.name); // Rectangle

Specifications

Browser compatibility

BCD tables only load in the browser

See also

JavaScript Constructors: What You Need to Know

A constructor is a special function that creates and initializes an object instance of a class. In JavaScript, a constructor gets called when an object is created using the new keyword.

The purpose of a constructor is to create a new object and set values for any existing object properties.

What Happens When A Constructor Gets Called?

When a constructor gets invoked in JavaScript, the following sequence of operations take place:

- A new empty object gets created.

- The this keyword begins to refer to the new object and it becomes the current instance object.

- The new object is then returned as the return value of the constructor.

JavaScript Constructor Examples

Here’s a few examples of constructors in JavaScript:

Using the «this» Keyword

When the this keyword is used in a constructor, it refers to the newly created object:

//Constructor function User() < this.name = 'Bob'; >var user = new User();Create Multiple Objects

In JavaScript, multiple objects can be created in a constructor:

//Constructor function User() < this.name = 'Bob'; >var user1 = new User(); var user2 = new User();In the above example, two objects are created using the same constructor.

Constructor with Parameters

A constructor can also have parameters:

//Constructor function User (name, age) < this.name = name; this.age = age; >var user1 = new User('Bob', 25); var user2 = new User('Alice', 27);In the above example, arguments are passed to the constructor during object creation. This allows each object to have different property values.

Constructor vs Object Literal

An object literal is typically used to create a single object whereas a constructor is useful for creating multiple objects:

//Constructor function User() < this.name = 'Bob'; >var user1 = new User(); var user2 = new User();Each object created using a constructor is unique. Properties can be added or removed from an object without affecting another one created using the same constructor. However, if an object is built using an object literal, any changes made to the variable that is assigned the object value will change the original object.

Object Prototype

Properties and methods can be added to a constructor using a prototype:

//Constructor function User() < this.name = 'Bob'; >let user1 = new User(); let user2 = new User(); //Adding property to constructor using prototype User.prototype.age = 25; console.log(user1.age); // 25 console.log(user2.age); // 25In the above example, two User objects are created using the constructor. A new property age is later added to the constructor using a prototype, which is shared across all instances of the User object.

Built-in Constructors

JavaScript has some built-in constructors, including the following:

var a = new Object(); var b = new String(); var c = new String('Bob') var d = new Number(); var e = new Number(25); var f = new Boolean(); var g = new Boolean(true);Although these constructors exist, it is recommended to use primitive data types where possible, such as:

var a = 'Bob'; var b = 25; var c = true;Strings, numbers and booleans should not be declared as objects since they hinder performance.

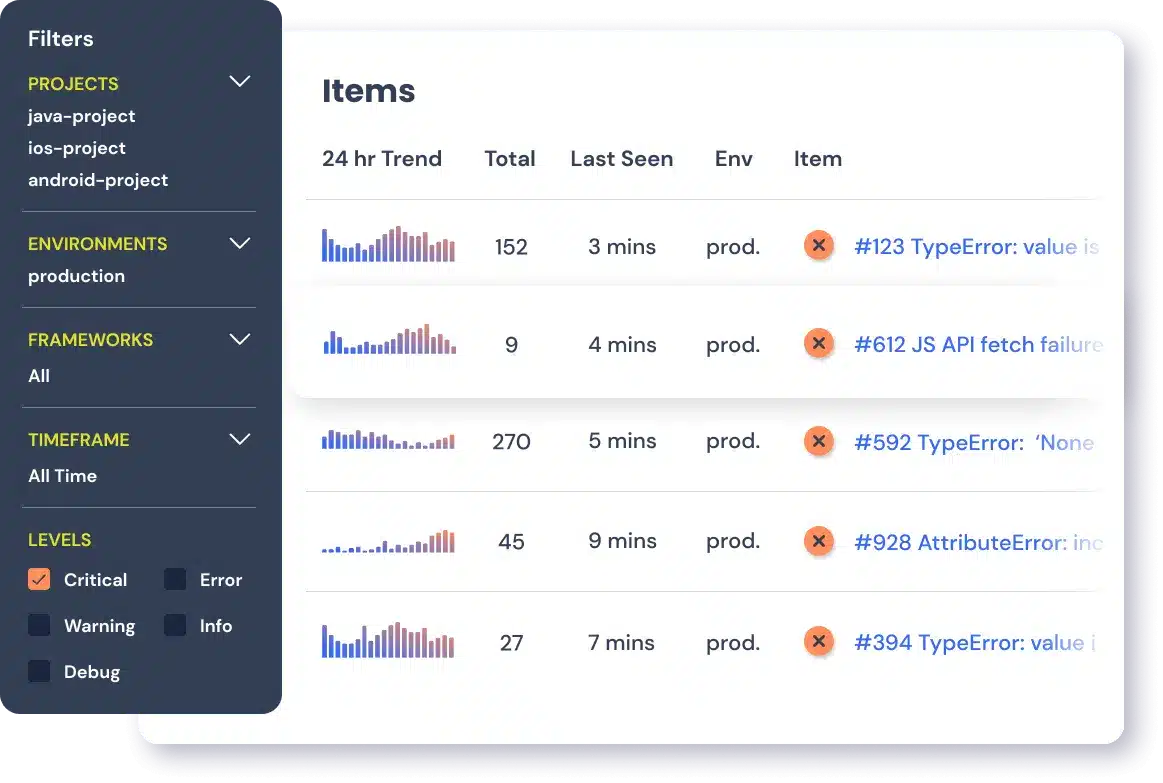

Track, Analyze and Manage Errors With Rollbar

Managing errors and exceptions in your code is challenging. It can make deploying production code an unnerving experience. Being able to track, analyze, and manage errors in real-time can help you to proceed with more confidence. Rollbar automates error monitoring and triaging, making fixing Java errors easier than ever. Sign Up Today!