JavaScript memory model demystified

I admit this title is a little clickbaity. Maybe a more accurate title should be “the JavaScript memory model that is implemented in the current version of V8 demystified (with a lot of oversimplification)”. V8 is very complex, and it has multiple ways to run code, and its various parts and pipelines that have been rewritten many times over the years so what I described today might become outdated tomorrow. Also this is not going to be a hardcore memory-related post which I am not really qualified to talk about.

There are a wealth of resources online claiming that in JavaScript primitive values are allocated on the stack while objects are allocated on the heap. This idea is false, at least this is not how the language is implemented in the majority of JavaScript engines I have seen. I am typing in this post so that I can link to it and save myself some time in the future.

TL;DR:#

- All JavaScript values are allocated on the heap accessed by pointers no matter if they are objects, arrays, strings or numbers (except for small integers i.e. smi in V8 due to pointer tagging).

- The stack only stores temporary, function-local and small variables (mostly pointers) and that’s largely unrelated to JavaScript types.

They are all implementation details#

First of all, the JavaScript language itself doesn’t mandate memory layout. You cannot find the term “Stack” or “Heap” used in the ECMAScript specification. In fact, I doubt you can find anything about memory layout in any language specification — even for C++, which is considered much more low-level than JavaScript, does not have the terms defined in its standard.

These are considered implementation details. Asking how JavaScript handles memory allocation is like asking if JavaScript is a compiled or interpreted language. It is a wrong question. What is interpreted or compiled is not the languages but instead implementations — we can easily build simple AST interpreter for JavaScript, or a Stack-based virtual machine, or static LLVM compiler to native code.

However being an implementation detail doesn’t mean it is a myth. You can trivially check this yourself by doing memory profiling in Chrome DevTools. If you want the ground truth, you can always look up the source code for the VM — at least for V8 it is all open-sourced.

All of the examples in this post are based on V8’s implementation. The V8 source code is from commit Id a684fc4c927940a073e3859cbf91c301550f4318.

(Almost) Everything is on the heap#

Contrary to common belief, primitive values are also allocated on the heap, just like objects.

If you don’t want to really dig into V8’s source code, there is an easy way that I can prove this to you.

- First use node —v8-options | grep -B0 -A1 stack-size to get the default size of stack in V8 on your machine. For me it outputs 864 KB.

- In a JavaScript file, create a giant string and use process.memoryUsage().heapUsed to get the size of the heap used.

This is a script that does that:

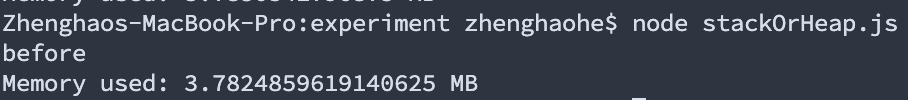

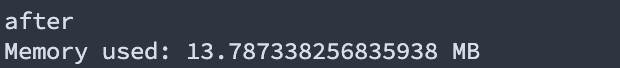

function memoryUsed() const mbUsed = process.memoryUsage().heapUsed / 1024 / 1024 console.log(`Memory used: $mbUsed> MB`); > console.log('before'); memoryUsed() const bigString = 'x'.repeat(10*1024*1024) console.log(bigString); // need to use the string otherwise the compiler would just optimize it into nothingness console.log('after'); memoryUsed() The size of the heap memory used before we created the string was 3.78 MB.

After I created a string of a size of 10 MB, the heap memory used increased to 13.78 MB

The difference between the before and after is precisely 10 MB. See the stack size we printed out before, it was only 864 KB — there is no way the stack can store such a string.

Primitive values are (mostly) reused#

String interning#

A quick question: for our 10 MB string created by ‘x’.repeat(10*1024*1024) , does an assignment (e.g. const anotherString = bigString ) duplicate the string in memory so that we end up with 20 MB in total allocated on the heap?

The answer is no — there will be no duplicate strings allocated. In general, and you probably already know this, assignments of JavaScript variables do not incur costs proportional to the size of the actual values — that is the point of pointers and JavaScript variables are (mostly) pointers.

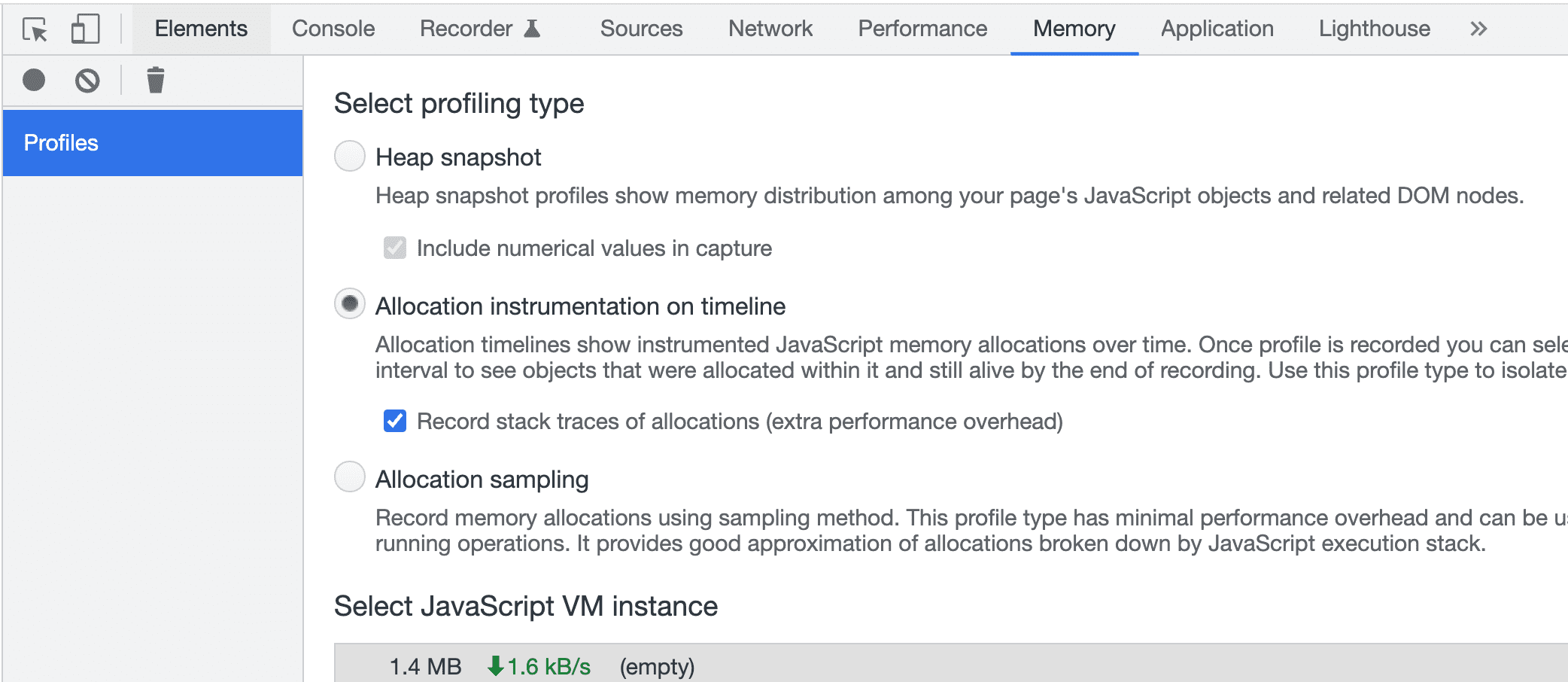

You can also check this via memory profiling using Chrome DevTools.

Create a html file with the following snippet:

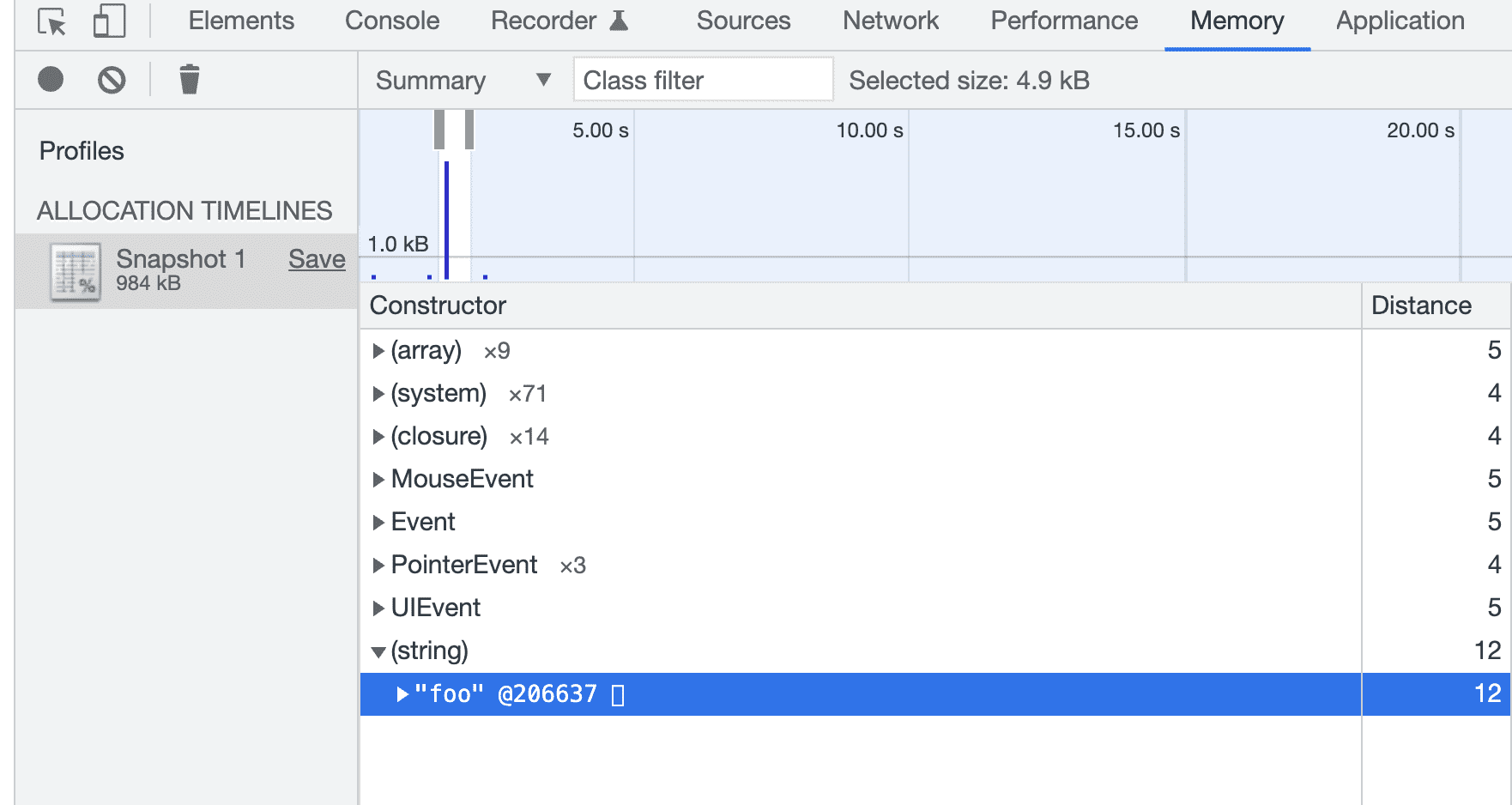

body> button id='btn'>btnbutton> script> const btn = document.querySelector('#btn') btn.onclick = () => < const string1 = 'foo' const string2 = 'foo' >body> Run the memory profiling and click on the button to create two variables with the same string value foo .

You will see that there is only one heap string allocated on the heap.

Chrome DevTools does not show where the pointers reside in memory but rather where they point to. Also the numbers you see e.g. @206637 do not represent raw memory addresses. If you want to inspect the actual memory, you need to use a native debugger.

This is called string interning. Inside V8, this is implemented via StringTable

explicit StringTable(Isolate* isolate); ~StringTable(); int Capacity() const; int NumberOfElements() const; // Find string in the string table. If it is not there yet, it is // added. The return value is the string found. HandleString> LookupString(Isolate* isolate, HandleString> key); // Find string in the string table, using the given key. If the string is not // there yet, it is created (by the key) and added. The return value is the // string found. template typename StringTableKey, typename IsolateT> HandleString> LookupKey(IsolateT* isolate, StringTableKey* key); Oddballs#

There are a special subset of primitive values called Oddball in V8.

type Null extends Oddball; type Undefined extends Oddball; type True extends Oddball; type False extends Oddball; type Exception extends Oddball; type EmptyString extends String; type Boolean = True|False; They are pre-allocated on the heap by V8 before the first line of your script runs — it doesn’t matter if your JavaScript program actually uses them down the road or not.

They are always reused — there is only one value of each Oddball type.

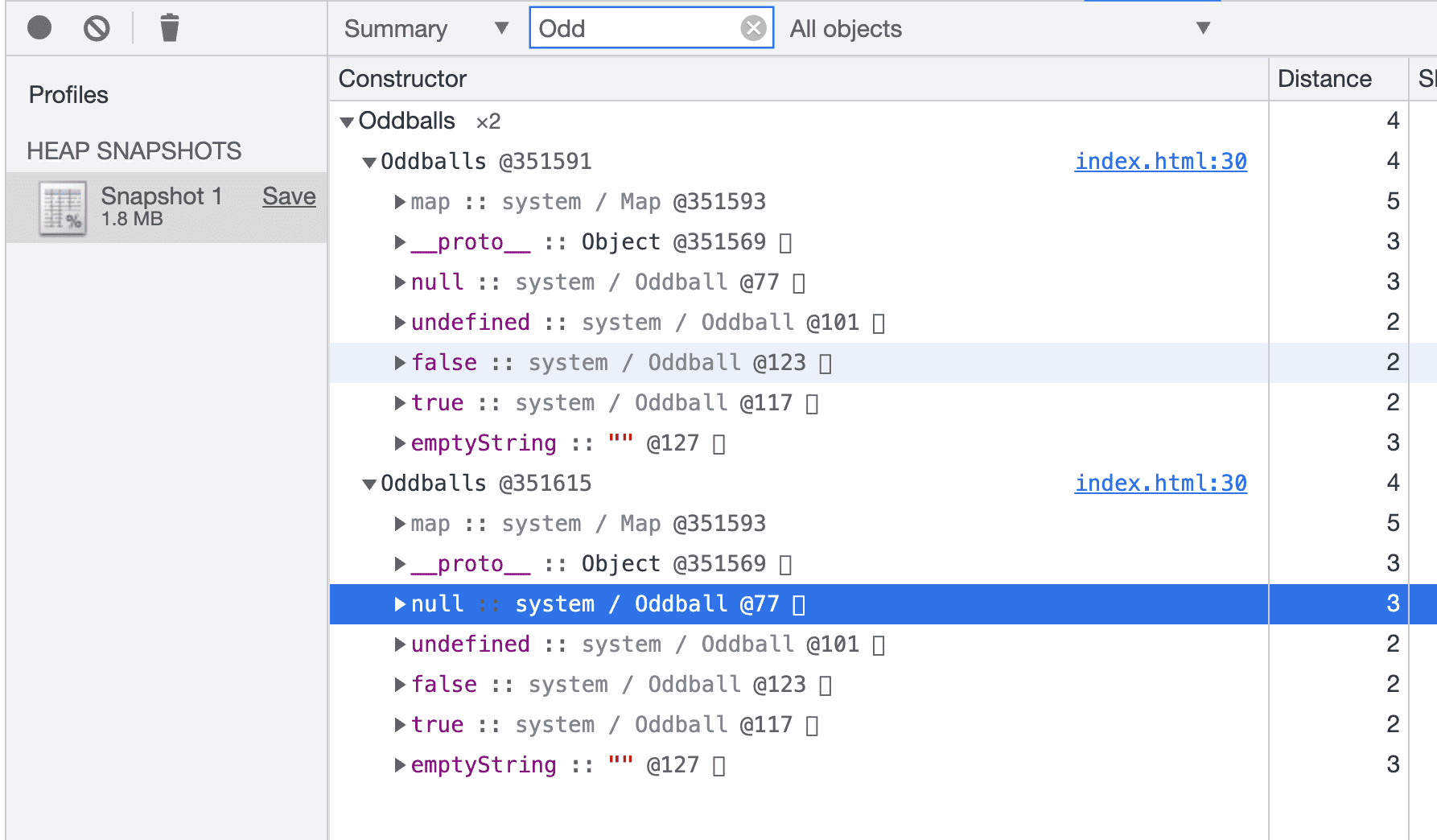

function Oddballs() this.undefined = undefined this.true = true this.false = false this.null = null this.emptyString = '' > const obj1 = new Oddballs() const obj2 = new Oddballs() Take a heap snapshot for this script above we get:

You see? Each Oddball type only has the same memory location on the heap even though the values are pointed by different objects’ properties.

When we are creating JavaScript variables that «have» Oddball values, we should think as if they were «summoned» in our JavaScript program — we cannot create or destroy them.

JavaScript variables are (mostly) pointers#

Digging deeper into the source code we can find that variables we create in our JavaScript program are just memory addresses that point to these C++ objects located on the heap.

For example, for undefined , the implementation in V8 is:

V8_INLINE LocalPrimitive> Undefined(Isolate* isolate) using S = internal::Address; using I = internal::Internals; I::CheckInitialized(isolate); S* slot = I::GetRoot(isolate, I::kUndefinedValueRootIndex); return LocalPrimitive>(reinterpret_castPrimitive*>(slot)); > And this is the implementation in V8 of GetRoot , which returns a memory address.

V8_INLINE static internal::Address* GetRoot(v8::Isolate* isolate, int index) internal::Address addr = reinterpret_castinternal::Address>(isolate) + kIsolateRootsOffset + index * kApiSystemPointerSize; return reinterpret_castinternal::Address*>(addr); > I wrote another post covering how JavaScript variables are implemented in more details.

Numbers are complicated#

In V8, integers ranging from -2³¹ to 2³¹-1 on a 64-bit architecture (the V8 term is smi ) are heavily optimized so they can be encoded inside of a pointer directly without the need to allocate additional storage for it. And it is not unique to V8 or JavaScript. A bunch of other languages like OCaml and Ruby does this too.

So technically, a smi can exist on the stack since they don’t need additional storage allocated on the heap, depending how the variables are declared:

- const a = 123 could be on the stack

- var a = 123 is on the heap, since it becomes a property of the global object, which is a fixed location in memory.

Also it depends on what the rest of the script is doing, and the runtime environment. The optimizing compiler keeps pointers held in registers as many as it can and it only spills to the stack during situations like registers run out.

Another complication about numbers is, unlike other types of primitive values, they might not get reused:

- For smi s, they are encoded as recognizably invalid pointers, which don’t point to anything, so the whole concept of «reusing» doesn’t really apply to them.

- For HeapNumber s (numbers that are not considered smi s):

- when they are pointed by object’s properties, it becomes a mutable HeapNumber , which allows updating the value without allocating a new HeapNumber every time. I believe this design decison is a beneficial tradeoff for the majority usage patterns at the cost of making HeapNumber s unshareable.

- other times they can be reused but only when that doesn’t incur extra performance overhead: for example, computations like 3 + 0.14 and 314/100 would result in two HeapNumber s of the value 3.14 allocated since checking if a HeapNumber of 3.14 already exists is not worth it.

To verify our theory, let’s try this snippet:

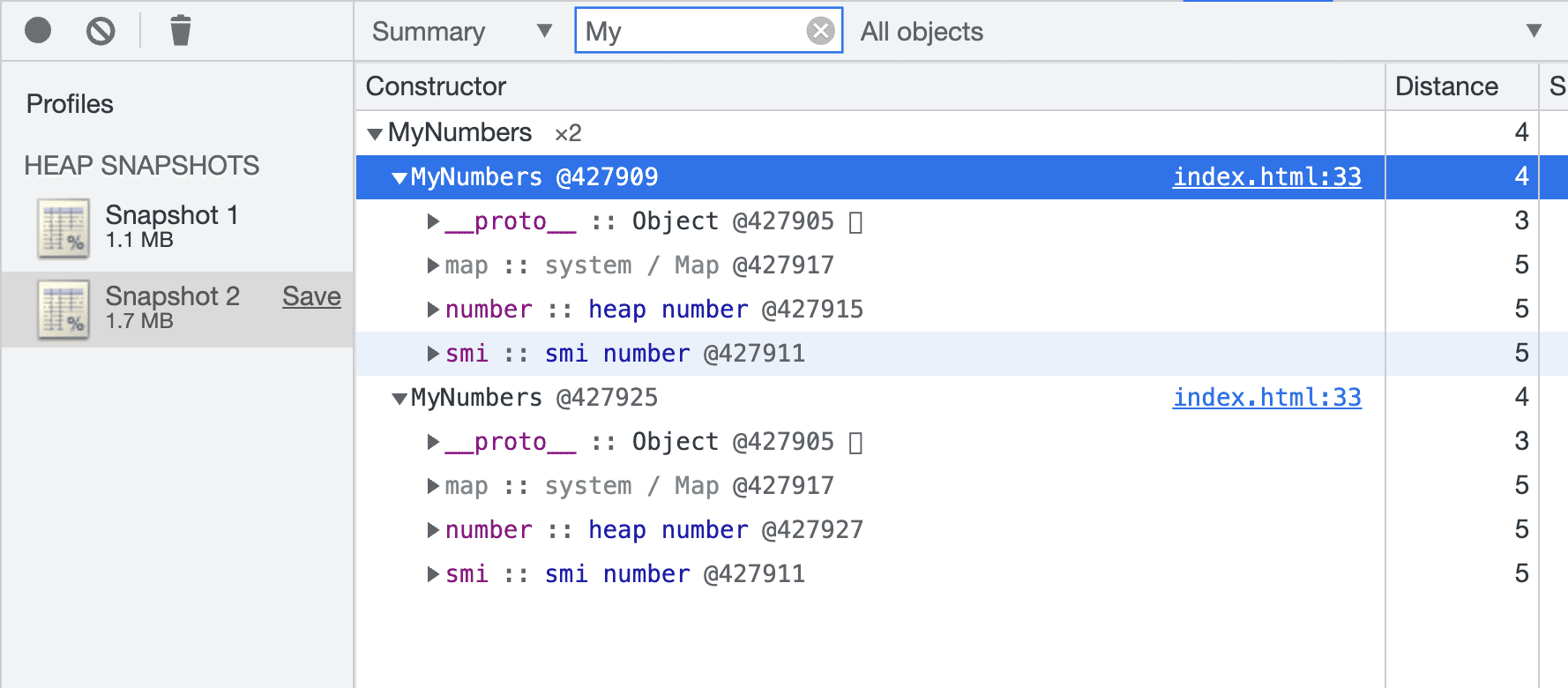

function MyNumbers() this.smi = 123 this.number = 3.14 > const num1 = new MyNumbers() const num2 = new MyNumbers() Take a heap snapshot and we get:

If you look closely enough, you would find that it seems like two smi s are «pointing» to the same memory location @427911 . smi s are immeidate integer values that point to nowhere. What caused this is the fact that they have the same bit pattern for the same value 123 and Chrome DevTools’s heap snapshots «blindly» treats them as pointers even though they are invalid pointers due to pointer tagging.

As to HeapNumber s, they are pointing to the different memory locations @427915 and @427927 , meaning they are not reused due to being a mutable HeapNumber .

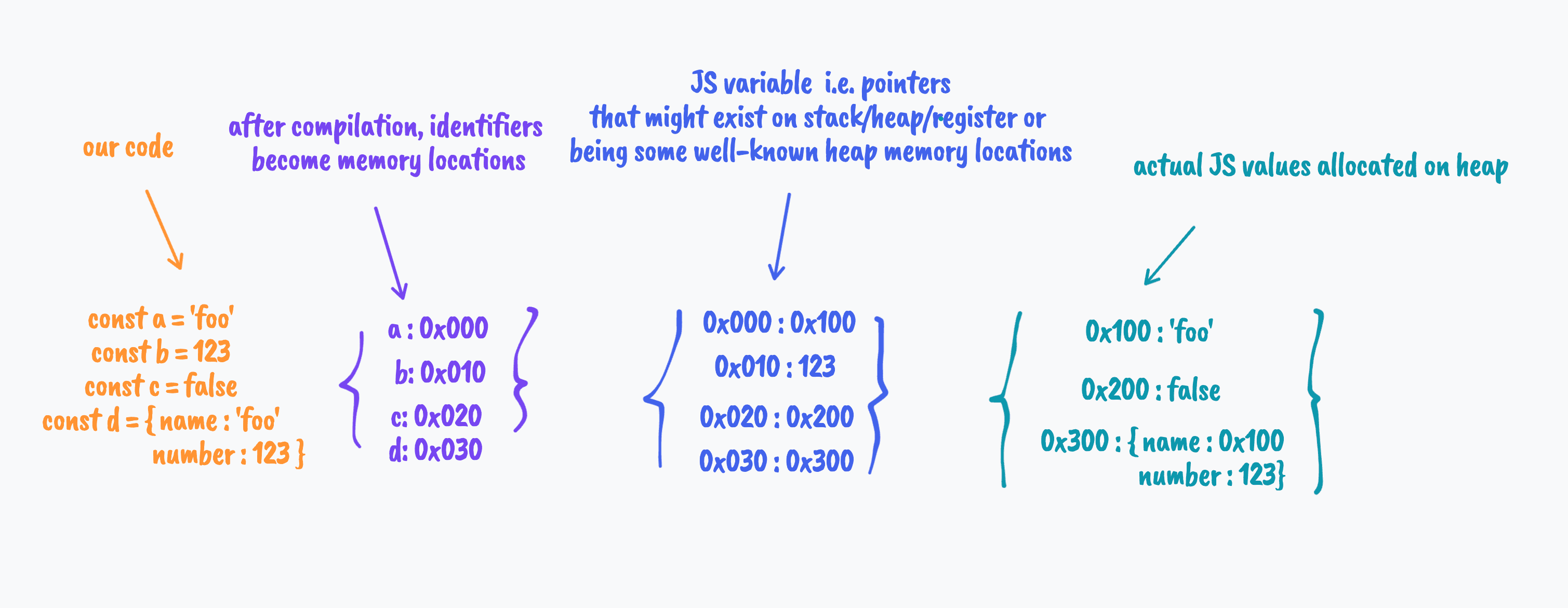

Put these together#

Here is a diagram that conceptually illustrates some possible memory layout in V8:

Closing thoughts#

Computer memory is an incredibly complex topic. I am by no means an expert on this topic. Nearly every answer to a question related to memory varies across compilers and processor architectures. For example, our variables are not always in memory (RAM) — they can be loaded directly in the destination registers, become part of instruction as an immediate value, or even get optimized entirely away into nothingness. The compiler can do whatever it wants as long as all the language semantics defined by the specification are preserved — the as-if rule.

If you are interested in learning low level details like memory layout, JavaScript is not a good tool for learning that because JavaScript engines like V8 are just too complicated and too powerful. Better start with C or C++ and using godbolt to understand how source code becomes machine code.