array — Efficient arrays of numeric values¶

This module defines an object type which can compactly represent an array of basic values: characters, integers, floating point numbers. Arrays are sequence types and behave very much like lists, except that the type of objects stored in them is constrained. The type is specified at object creation time by using a type code, which is a single character. The following type codes are defined:

- It can be 16 bits or 32 bits depending on the platform.

Changed in version 3.9: array(‘u’) now uses wchar_t as C type instead of deprecated Py_UNICODE . This change doesn’t affect its behavior because Py_UNICODE is alias of wchar_t since Python 3.3.

The actual representation of values is determined by the machine architecture (strictly speaking, by the C implementation). The actual size can be accessed through the array.itemsize attribute.

The module defines the following item:

A string with all available type codes.

The module defines the following type:

class array. array ( typecode [ , initializer ] ) ¶

A new array whose items are restricted by typecode, and initialized from the optional initializer value, which must be a list, a bytes-like object , or iterable over elements of the appropriate type.

If given a list or string, the initializer is passed to the new array’s fromlist() , frombytes() , or fromunicode() method (see below) to add initial items to the array. Otherwise, the iterable initializer is passed to the extend() method.

Array objects support the ordinary sequence operations of indexing, slicing, concatenation, and multiplication. When using slice assignment, the assigned value must be an array object with the same type code; in all other cases, TypeError is raised. Array objects also implement the buffer interface, and may be used wherever bytes-like objects are supported.

Raises an auditing event array.__new__ with arguments typecode , initializer .

The typecode character used to create the array.

The length in bytes of one array item in the internal representation.

Append a new item with value x to the end of the array.

Return a tuple (address, length) giving the current memory address and the length in elements of the buffer used to hold array’s contents. The size of the memory buffer in bytes can be computed as array.buffer_info()[1] * array.itemsize . This is occasionally useful when working with low-level (and inherently unsafe) I/O interfaces that require memory addresses, such as certain ioctl() operations. The returned numbers are valid as long as the array exists and no length-changing operations are applied to it.

When using array objects from code written in C or C++ (the only way to effectively make use of this information), it makes more sense to use the buffer interface supported by array objects. This method is maintained for backward compatibility and should be avoided in new code. The buffer interface is documented in Buffer Protocol .

“Byteswap” all items of the array. This is only supported for values which are 1, 2, 4, or 8 bytes in size; for other types of values, RuntimeError is raised. It is useful when reading data from a file written on a machine with a different byte order.

Return the number of occurrences of x in the array.

Append items from iterable to the end of the array. If iterable is another array, it must have exactly the same type code; if not, TypeError will be raised. If iterable is not an array, it must be iterable and its elements must be the right type to be appended to the array.

Appends items from the string, interpreting the string as an array of machine values (as if it had been read from a file using the fromfile() method).

New in version 3.2: fromstring() is renamed to frombytes() for clarity.

Read n items (as machine values) from the file object f and append them to the end of the array. If less than n items are available, EOFError is raised, but the items that were available are still inserted into the array.

Append items from the list. This is equivalent to for x in list: a.append(x) except that if there is a type error, the array is unchanged.

Extends this array with data from the given unicode string. The array must be a type ‘u’ array; otherwise a ValueError is raised. Use array.frombytes(unicodestring.encode(enc)) to append Unicode data to an array of some other type.

Return the smallest i such that i is the index of the first occurrence of x in the array. The optional arguments start and stop can be specified to search for x within a subsection of the array. Raise ValueError if x is not found.

Changed in version 3.10: Added optional start and stop parameters.

Insert a new item with value x in the array before position i. Negative values are treated as being relative to the end of the array.

Removes the item with the index i from the array and returns it. The optional argument defaults to -1 , so that by default the last item is removed and returned.

Remove the first occurrence of x from the array.

Reverse the order of the items in the array.

Convert the array to an array of machine values and return the bytes representation (the same sequence of bytes that would be written to a file by the tofile() method.)

New in version 3.2: tostring() is renamed to tobytes() for clarity.

Write all items (as machine values) to the file object f.

Convert the array to an ordinary list with the same items.

Convert the array to a unicode string. The array must be a type ‘u’ array; otherwise a ValueError is raised. Use array.tobytes().decode(enc) to obtain a unicode string from an array of some other type.

When an array object is printed or converted to a string, it is represented as array(typecode, initializer) . The initializer is omitted if the array is empty, otherwise it is a string if the typecode is ‘u’ , otherwise it is a list of numbers. The string is guaranteed to be able to be converted back to an array with the same type and value using eval() , so long as the array class has been imported using from array import array . Examples:

array('l') array('u', 'hello \u2641') array('l', [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]) array('d', [1.0, 2.0, 3.14])

Packing and unpacking of heterogeneous binary data.

Packing and unpacking of External Data Representation (XDR) data as used in some remote procedure call systems.

The NumPy package defines another array type.

Списки в Python: что это такое и как с ними работать

Рассказали всё самое важное о списках для тех, кто только становится «змееустом».

Иллюстрация: Оля Ежак для Skillbox Media

Любитель научной фантастики и технологического прогресса. Хорошо сочетает в себе заумного технаря и утончённого гуманитария. Пишет про IT и радуется этому.

Сегодня мы подробно поговорим о, пожалуй, самых важных объектах в Python — списках. Разберём, зачем они нужны, как их использовать и какие удобные функции есть для работы с ними.

В статье есть всё, что начинающим разработчикам нужно знать о списках в Python:

Что такое списки

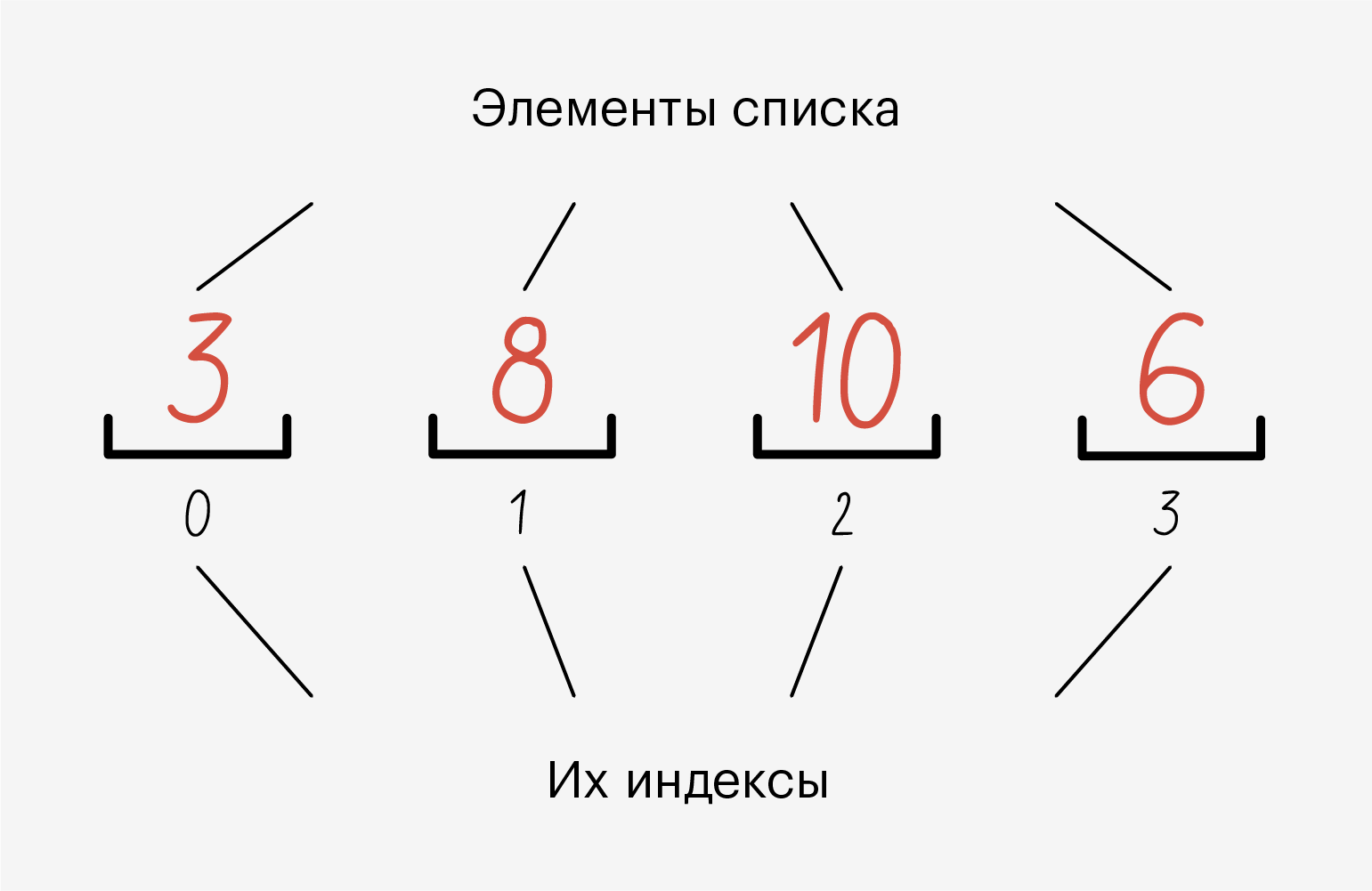

Список (list) — это упорядоченный набор элементов, каждый из которых имеет свой номер, или индекс, позволяющий быстро получить к нему доступ. Нумерация элементов в списке начинается с 0: почему-то так сложилось в C, а C — это база. Теорий на этот счёт много — на «Хабре» даже вышло большое расследование 🙂

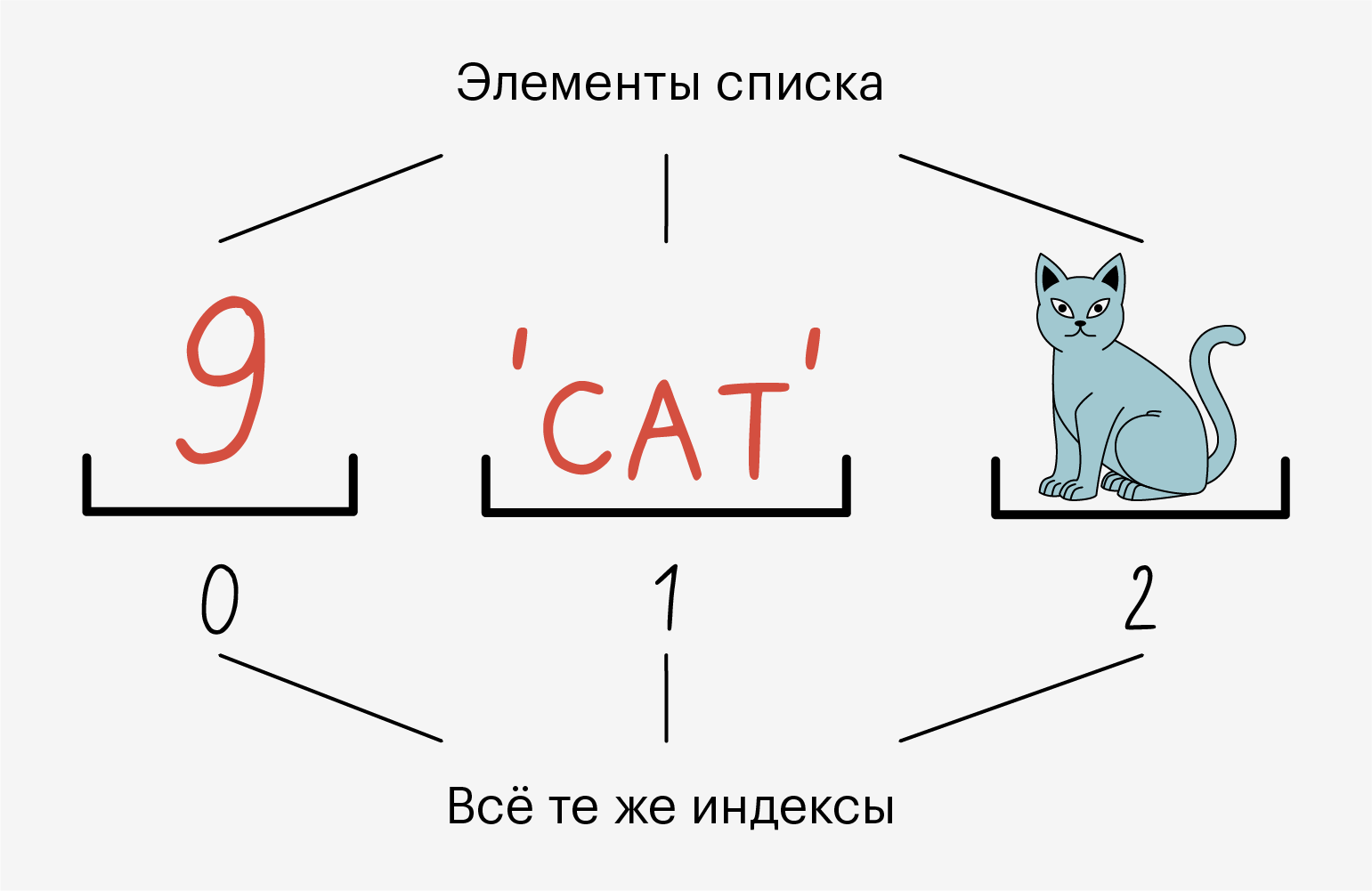

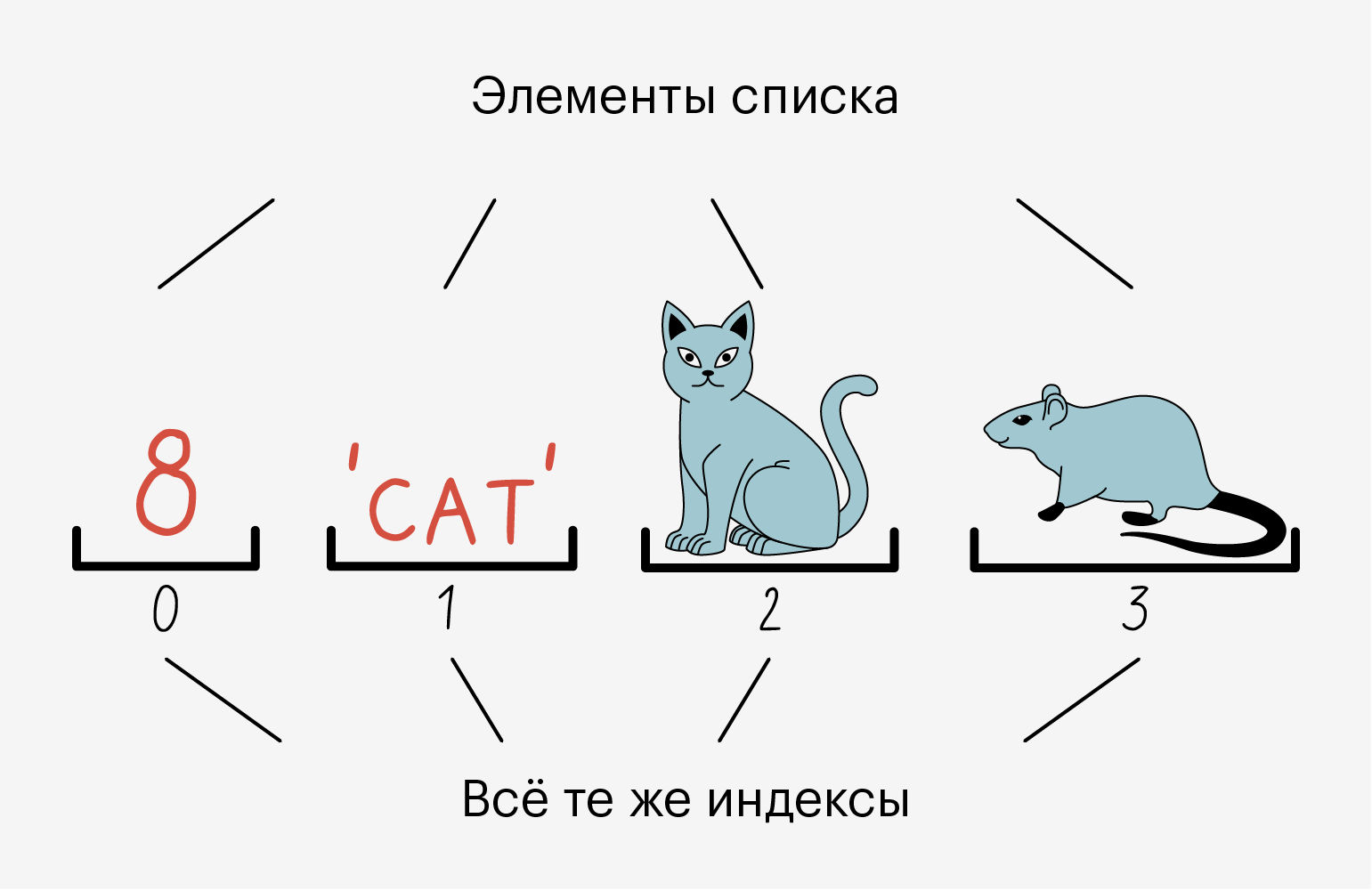

В одном списке одновременно могут лежать данные разных типов — например, и строки, и числа. А ещё в один список можно положить другой и ничего не сломается:

Все элементы в списке пронумерованы. Мы можем без проблем узнать индекс элемента и обратиться по нему.

Списки называют динамическими структурами данных, потому что их можно менять на ходу: удалить один или несколько элементов, заменить или добавить новые.

Когда мы создаём объект list, в памяти компьютера под него резервируется место. Нам не нужно переживать о том, сколько выделяется места и когда оно освобождается, — Python всё сделает сам. Например, когда мы добавляем новые элементы, он выделяет память, а когда удаляем старые — освобождает.

Под капотом списков в Python лежит структура данных под названием «массив». У массива есть два важных свойства: под каждый элемент он резервирует одинаковое количество памяти, а все элементы следуют друг за другом, без «пробелов».

Однако в списках Python можно хранить объекты разного размера и типа. Более того, размер массива ограничен, а размер списка в Python — нет. Но всё равно мы знаем, сколько у нас элементов, а значит, можем обратиться к любому из них с помощью индексов.

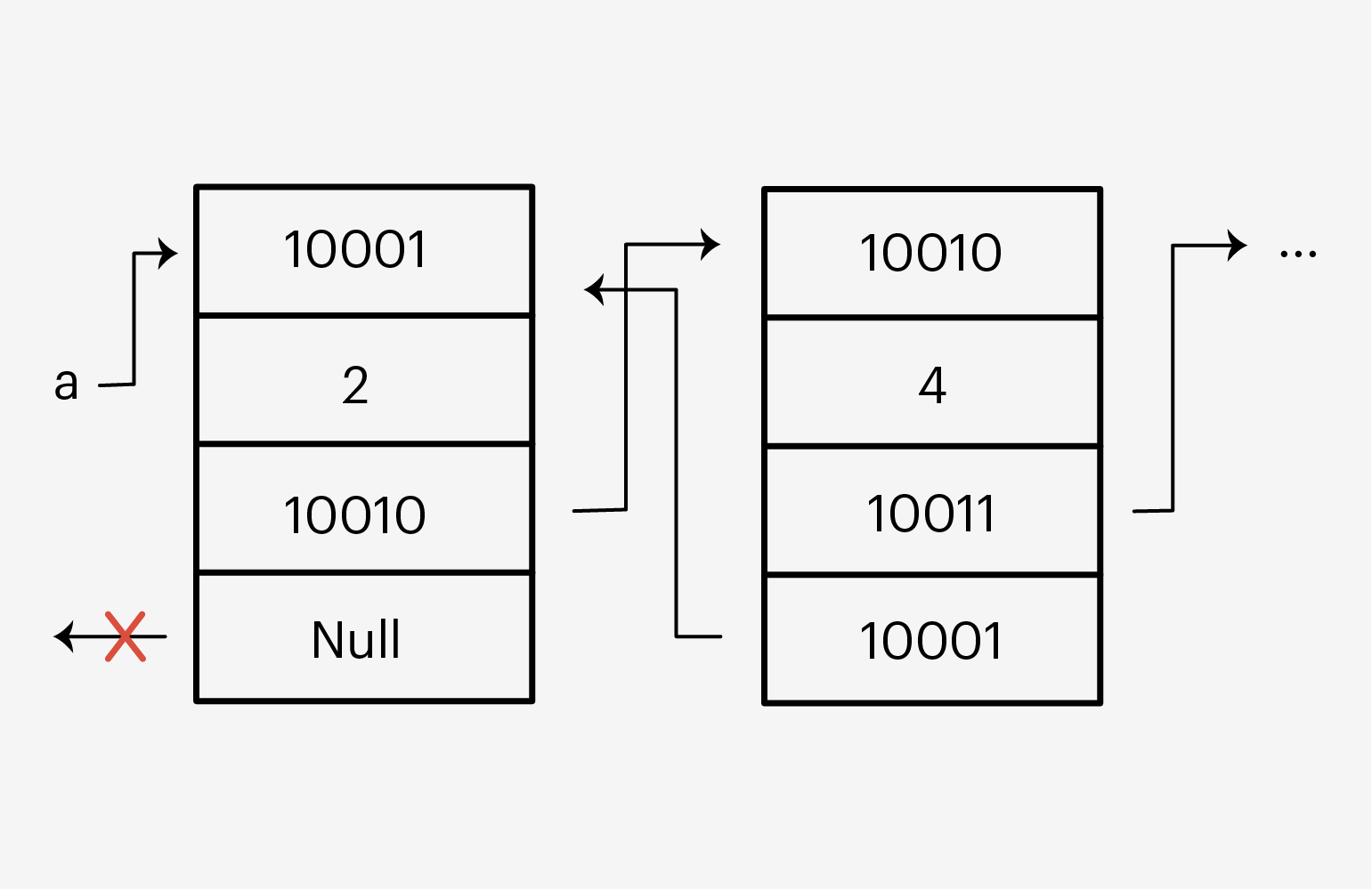

И тут есть небольшой трюк: списки в Python представляют собой массив ссылок. Да-да, решение очень элегантное — каждый элемент такого массива хранит не сами данные, а ссылку на их расположение в памяти компьютера!

Как создать список в Python

Чтобы создать объект list, в Python используют квадратные скобки — []. Внутри них перечисляют элементы через запятую:

Операции со списками

Если просто хранить данные в списках, то от них будет мало толку. Поэтому давайте рассмотрим, какие операции они позволяют выполнить.

Индексация

Доступ к элементам списка получают по индексам, через квадратные скобки []:

Каждый элемент списка имеет четыре секции: свой адрес, данные, адрес следующего элемента и адрес предыдущего. Если мы получили доступ к какому-то элементу, мы без проблем можем двигаться вперёд-назад по этому списку и менять его данные.

Поэтому, когда мы присвоили списку b список a, то на самом деле присвоили ему ссылку на первый элемент — по сути, сделав их одним списком.

Объединение списков

Иногда полезно объединить два списка. Чтобы это сделать, используют оператор +:

insert()

Добавляет новый элемент по индексу:

clear()

Удаляет все элементы из списка и делает его пустым:

index()

Возвращает индекс элемента списка в Python:

Если элемента нет в списке, выведется ошибка:

a = [1, 2, 3] print(a.index(4)) Traceback (most recent call last): File "", line 1, in ValueError: 4 is not in list

pop()

Удаляет элемент по индексу и возвращает его как результат:

a = [1, 2, 3] print(a.pop()) print(a) >>> 3 >>> [1, 2]

Мы не передали индекс в метод, поэтому он удалил последний элемент списка. Если передать индекс, то получится так:

a = [1, 2, 3] print(a.pop(1)) print(a) >>> 2 >>> [1, 3]

count()

Считает, сколько раз элемент повторяется в списке:

a = [1, 1, 1, 2] print(a.count(1)) >>> 3

sort()

a = [4, 1, 5, 2] a.sort() # [1, 2, 4, 5]

Если нам нужно отсортировать в обратном порядке — от большего к меньшему, — в методе есть дополнительный параметр reverse:

a = [4, 1, 5, 2] a.sort(reverse=True) # [5, 4, 2, 1]

reverse()

Переставляет элементы в обратном порядке:

a = [1, 3, 2, 4] a.reverse() # [4, 2, 3, 1]

copy()

a = [1, 2, 3] b = a.copy() print(b) >>> [1, 2, 3]

Для того чтобы быстро находить нужные методы во время работы, пользуйтесь этой шпаргалкой:

| Метод | Что делает |

|---|---|

| a.append(x) | Добавляет элемент x в конец списка a. Если x — список, то он появится в a как вложенный |

| a.extend(b) | Добавляет в конец a все элементы списка b |

| a.insert(i, x) | Вставляет элемент x на позицию i |

| a.remove(x) | Удаляет в a первый элемент, значение которого равно x |

| a.clear() | Удаляет все элементы из списка a и делает его пустым |

| a.index(x) | Возвращает индекс элемента списка |

| a.pop(i) | Удаляет элемент по индексу и возвращает его |

| a.count(x) | Считает, сколько раз элемент повторяется в списке |

| a.sort() | Сортирует список. Чтобы отсортировать элементы в обратном порядке, нужно установить дополнительный аргумент reverse=True |

| a.reverse() | Возвращает обратный итератор списка a |

| a.copy() | Создаёт поверхностную копию списка. Для создания глубокой копии используйте метод deepcopy из модуля copy |

Что запомнить

Лучше не учить это всё, а применять на практике. А ещё лучше — попытаться написать каждый метод самостоятельно, не используя никакие встроенные функции.

Сколько бы вы ни писали код на Python, всё равно придётся подсматривать в документацию и понимать, какой метод что делает. И для этого есть разные удобные сайты — например, полный список методов можно посмотреть на W3Schools.

Больше интересного про код в нашем телеграм-канале. Подписывайтесь!

Читайте также: